While in school, Zeverin Emagalit studied philosophy — which literally translates to “love of knowledge.”

Emagalit has always loved to learn and pursue his various interests, bringing him all over the world to study languages, philosophy and cultures. He said this first great love eventually helped him find his second.

At 16, Emagalit attended a meditation retreat near his home in eastern Uganda. While there, he clasped his hands together, praying to God to find his calling in life.

“Teaching is the answer I got,” Emagalit said. “And I never regretted it.”

From that point, Emagalit said he voraciously pursued his education. He earned his undergraduate degree from Makerere University in Kampala, Uganda, later moving to study philosophy in Rome and education at the University of London.

As he truly valued independence, Emagalit said he refused to let his parents pay for his education. Instead, he worked through school to take care of his own tuition, including working in a factory in Ulm, Germany, that specialized in creating water heaters.

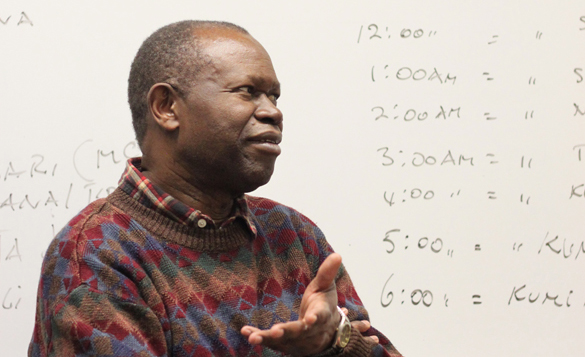

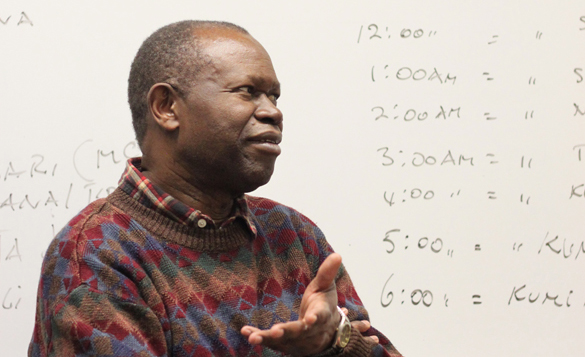

Emagalit has taught Kiswahili at SUNY New Paltz since 1994. Though he originally applied to teach philosophy, which he had taught at both Ulster and Dutchess community colleges and Mount Saint Mary College, he said he was later approached by professors in the Department of Black Studies to fill the position for the elementary Kiswahili courses.

Though he said the program started off small, sometimes with just two or three students in a class, it eventually grew after connecting with the other foreign language departments, reaching a high enrollment rate of 123 students two years ago.

Emagalit is fluent in five languages: Ateso, Luo – languages spoken in eastern Uganda and western Kenya – as well as Kiswahili, English and Italian.

He said his experience with the different languages has given him insight into the different patterns that exist in them.

Fourth-year international relations major Charlotte Mitchell took Emagalit’s class two years ago and said the course was ultimately one of the factors that brought her to study abroad in Kenya.

“His class isn’t easy and he teaches in a somewhat unconventional manner,” Mitchell said. “But I learned a lot by taking the class with [Emagalit] in terms of reading and writing the language. All of [Emagalit’s] tests are translating sentences back and forth from Swahili to English [which was] helpful because you really got an understanding of the Swahili sentence structure, which is much different than any of the romance languages.”

Emagalit believes the best way to educate, especially when teaching a language, is through storytelling and conversation. He said the images conjured through those methods are not only powerful enough to resonate with students and hold their attention but also to lure out the students who are too shy to speak during class.

He said that’s why he tries to speak with his students about the subjects that interest him — economics, finance, philosophy, ethics and various humanitarian endeavors — to offer them more than just a simple crash course in the language.

“I teach you language, sure,” Emagalit said. “But you come to university to train your mind to solve problems. I’m here to help you think.”

Emagalit said these exercises are the foundations of his lessons. He tries to regularly pose challenges for his students to work through, the kind that will benefit them not only in their studies of language, but also in their other endeavors.

“I don’t want my students to be afraid of ideas or making mistakes,” Emagalit said. “They will only help you in the future.”

When teaching a lesson on future tense to his Elementary Kiswahili class, Emagalit asks his students where they think they will be 10 years from now.

Some have ideas or hopes for their futures, but others just don’t know.

That conversation and talking about the future allows him to move his lesson forward — How do the students then express that in Kiswahili?

He said he wants them to interact and communicate real sentiments in the language to help them fall in love with it, at least a little bit.

“People love to see what you’re enthusiastic about, what gives you fire,” Emagalit said. “You want to get [the students] excited, to show passion. Then you can educate.”