On Feb. 22, the SUNY New Paltz School of Education held a virtual workshop led by Dr. Yolanda Sealy-Ruiz called, “(Re)Shaping, (Re)Shifting, and (Re)Imagining Our Work Through Racial Literacy.” The event was part of the first annual School of Education guest speaker series.

Dr. Ruiz shared insight into the Racial Literacy Project, a 14 year initiative driven by national scholars, teachers and students facilitating conversations and performances around race and other issues involving diversity. The project originated from the Columbia University’s Teacher College Racial Literacy Roundtable series, founded by Dr. Ruiz and three of her master’s students. The roundtable series created a forum for discussing critical race issues in regards to society, education and institutions.

Racial literacy in educational practices is defined by Ruiz in the workshop as a practice and skill in which students examine racism and its presence in American history, institutions and lived experiences. An important development in education theory, racial literacy works when it is put into practice. This transition process involves the “(Re)Shaping” and “(Re)Shifting” of work through advocacy while “(Re)Imagining” education comes into play once work and cultural change is reflected.

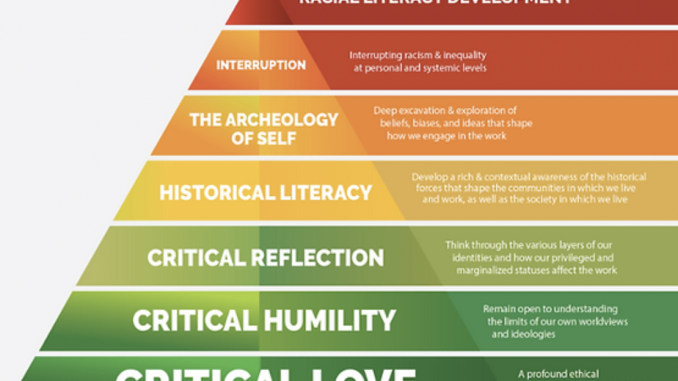

For practicality purposes, Ruiz broke down racial literacy developments into six components: interruption, archeology of self, historical literacy, critical reflection, critical humility and critical love. Ranked in the form of a pyramid, each component stands as a guide to how one can use the theory to change practice. Thus, racial literacy is learned and applied systematically, working through each step to address problems and educate effectively.

Articulate and dedicated, Dr. Ruiz walked participants through what racial literacy means both in theory and in practice while living through what she described as “turbulent times.” Turbulent times refers to both sociopolitical events and personal experiences that shape how we as individuals perceive the world and our institutions. Racial literacy is at its greatest importance in situations regarding Americans who are either ignorant to or against the inclusion of racial discourse in education.

The workshop did not rely solely on Dr. Ruiz’s narration; by engaging participants, she was able to demonstrate how the development of racial literacy worked. Ruiz began with having participants voice what in their lives were causing them grief and strife, with responses ranging from workloads to microaggressions to lack of sleep. After reading aloud most of the responses, Ruiz drew connections between turbulence within self to turbulence within the world, which all relates back to turbulence within education.

Describing herself as a “wounded healer,” Ruiz explained how she refuses to let her experiences with racism and grief stop her from seeking to heal what racism interrupts and destroys. Her honesty and humility through the exercise made the workshop more grounded. Racial literacy is a new concept with many nuances, but is also far-reaching and important for individuals with diverse experiences and backgrounds to learn, implement and value.

Following the first exercise, Ruiz had participants voice themselves once again. But this time, she had those willing express what in their lives were giving them strength. Answers, once again, were diverse, ranging from the freshly-fallen snow to chosen family to prayer. Using the quick rate of responses to make her point, Ruiz connected people’s self-awareness of both good and bad to the archeology of self, one of the components of developing racial literacy.

The archeology of self is an action-oriented process that develops a keen understanding of oneself in order to understand systems. Ruiz applied the archeology of self to educational situations by explaining how teachers committed to the process are able to dig up preconceived notions that are racially motivated and undermining. The process is difficult and requires a high degree of effort, but to work as an educator is to accept the obligation to lead by example when it comes to historical truth, racial discourses and advocacy for equality.

The point that Ruiz was working to form through all her explanations of racial literacy development, practicality and the archeology of self was regarding racist/anti-racist discourse. Conversations about American societal and educational problems, according to Dr. Ruiz, are broken down into two notions: problems are either perceived as being rooted in groups of people or perceived as being rooted in power and policies. The first being clearly defined as racist and the latter understood to be anti-racist, Ruiz made the firm point that there was little room for nuance or argument. Thus, racial literacy “activates the anti-racist stance, the only leg on which to stand.”

Education has always been a battlefield for equality. Educators are in a highly influential position for the students they teach, as well as themselves, as their position is subject to constant debate over the nuances of activism and education. Through racial literacy and the archeology of self, there is a foundation for cultural change through reflection, critical analysis of one’s role and commitment to equality. As Ruiz concluded, “We have to decide that we will be the change.”