If there’s a simple way to understand astrobiology, it’s by asking two questions: are we alone in the universe and where do we come from?

On Tuesday, Oct. 25, Caleb Scharf, Ph.D., director of the Columbia Astrobiology Center at Columbia University, delivered a lecture entitled, “Astrobiology: The Science of Life in The Universe.” The lecture, held in the Coykendall Science Building Auditorium, was the second event of the academic year for the SUNY New Paltz Harrington STEM Lecture Series.

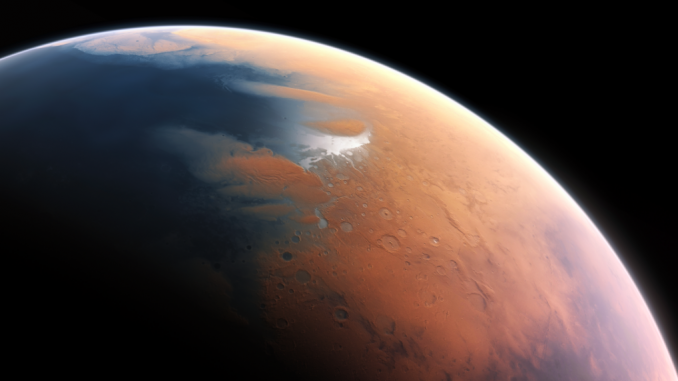

Scharf broke down his presentation by likely candidates for life in the universe, including Mars, icy moons, exoplanets and other bodies. He said that while humanity’s primary fascination has been with the Red Planet, moons in the outer regions of the solar system may hold the key to understanding the inception of life.

“We could be the first example of life in universe, even with thousands of other forms of life,” Scharf said. “But if you could find one independent example of abiogenesis, it would change the results dramatically.”

In analyzing NASA’s explorations of Mars and Enceladus and Titan, moons revolving around Saturn and Jupiter, respectively, Scharf argued that the life present there might not fit with the public’s perception of life in space. Considering the case of Enceladus, which he referred to as a 300-mile “puzzle,” he cited information provided by the Cassini spacecraft mission, which has orbited Saturn since 2004. He pointed to potential evidence of Enceladus having an interior global ocean, which scientists believe exists since the moon has an unusual orbit due to surface geysers that are visible in photographs.

“We have evidence that suggests there is 15 times the volume of Earth’s oceans in these outer solar system icy bodies,” Scharf said. “However, there aren’t any plans to investigate them further, which has disappointed some in the community.”

While addressing exoplanets, Scharf applauded the Kepler spacecraft mission as one of NASA’s best projects. According to data from the mission in 2015, Kepler has identified over 3,500 planets around other stars. This has allowed for scientists to consider planetary candidates based on their measurements, size and orbital period.

The relation between atmospheric and surface conditions on planets has intrigued scientists so much that they have begun to compute what conditions are necessary for life to exist. Scharf has been actively involved with the Goddard Institute for Space Studies, which is responsible for the atmosphere-ocean climate model named Rocke3d. The program, which relies on complicated code to calibrate its models, has dispelled previous expectations for life on planets. These include whether or not size or distance from the Sun can play decisive roles in the existence of life.

“We have to be careful about interpreting data from exoplanets. Climate is a difficult thing to measure,” Scharf said.

He concluded his talk by explaining the concepts of the ‘Great Filter’ and the Fermi paradox, which offers a possible explanation for why we haven’t found life in the universe. He said that finding life on Mars could be bad because maybe we haven’t gone through the Great Filter, which theorizes that something always goes wrong and life never gets past a certain point. In accepting this, humans essentially admit that life is not everlasting and that an event in the future will bring an end to life as it’s currently known.