Third-year visual arts major Hannah Ward can go from sketching fruit to studying vertebrate anatomy – in the same day.

One subject, she said, requires a great deal of memorizing detail while the other demands inventive problem solving and development of both technique and a point of view. By combining these skills, Ward unearthed more than just a passion – she discovered a potential career in medical illustrations.

“At times, art and science may seem to be from two completely different worlds of thinking,” she said. “But I love the way that this career is able to unify them and, at the same time, really help and educate others.”

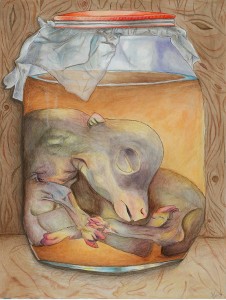

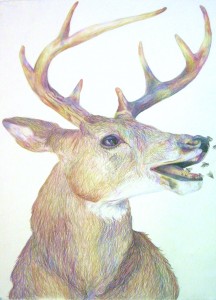

As a young child, Ward said she enjoyed all aspects of art, especially painting and drawing. As she grew as an artist, she said she began to develop a common theme within her work that focused on the concept of beauty in connection with decay. Often drawing animals or people, she said she started to incorporate anatomical subject matter and themes into almost everything she created.

Although she originally saw her passion for art as a hobby, she said her dedication as a student has led her into new artistic territories that could one day include textbook illustrations, making prosthetics, facial reconstructions for forensic sciences, instructive animations and even scientific research.

“I’ve always had a great interest in science,” she said. “When I heard that such [careers] existed, I realized that so much of my work was scientifically based and that I would love to pursue the field. I think scientists and artists are both observers and the stretch isn’t as ridiculous as it may sound.”

“I’ve always had a great interest in science,” she said. “When I heard that such [careers] existed, I realized that so much of my work was scientifically based and that I would love to pursue the field. I think scientists and artists are both observers and the stretch isn’t as ridiculous as it may sound.”

As both an art and science student, Ward said she is often required to completely alter her learning style with each class she attends. However, because her science lab courses require mostly observation and dissection, they have helped to train her eye and bridge the two subjects.

According to Ward, her career goals usually seem completely foreign and surprising at first mention. The idea of mixing art and science, she said, can seem taboo not only to students outside of the art program, but within it as well.

“Most artists are really uncomfortable with the fact that your freedom is pretty limited in this career,” she said. “Technique and observation have priority over your creativity.”

In order to remain inspired, Ward said she likes to capture the complexity of nature in her work. However, she said there often comes a point when she needs a mental break from her technical work to allow her imagination to run free.

Initially starting college strictly as an art student, Ward said she now classifies her potential career as both an applied science and an applied art.

“I’m definitely more passionate about my artwork, but I understand why it would be viewed as applied science,” she said. “When people look through a textbook or a medical journal, they’re studying the image or diagram and not really thinking about there being a person responsible for it.”

At her current undergraduate level, Ward said she is often hit with a heavy workload, a necessity in order to develop a strong background in both studio art and biology.

At SUNY New Paltz, Ward said there is no specific course geared toward this career path, but that hasn’t slowed her down.

“It’s not something that people typically have a chance to begin at an undergraduate level,” she said. “I have basically tried to gear my portfolio and research toward the requirements that I need for graduate school.”

Currently, there are only five graduate schools in North America that will certify students for Ward’s desired careers – four in the U.S. and one in Canada. Some of which, she said, only accept four or five students per semester.

To be considered for these programs, Ward said portfolios must include particular examples of figure drawing, graphic design, sculpture, a range of color media and the completion of a specific set of art classes.

In addition to having a firm knowledge and background in art, Ward said students must have taken general biology and chemistry, comparative vertebrate anatomy, vertebrate physiology and at least one other upper division biology class.

“I’m required to have much of the same training and motivation for research as an individual from any medical profession,” she said.

If accepted to one of these graduate programs, Ward said she would be able to take science-based studio art courses, including drawing from actual surgeries, dissections and autopsies.

With hard work and preparation, Ward said she first plans to pursue biological research involving illustrations for animal studies. However, she said she finds it satisfying knowing that if she ever wants to switch over to a career in making prosthetics to assist people in a different way, she can do that too.

“I love that I can use my artistic skills to both help others and form a career for myself,” she said. “Historically, fine arts and studying nature have always gone hand-in-hand. I think this job just takes it to the next level.”