Last month, a petition on change.org began to circulate around local New Paltz social media circles. Its goal: to rename the SUNY New Paltz Hasbrouck Dining Hall after Darold Thompson, a longtime and beloved employee at the dining hall who tragically passed away in August. The petition garnered enough student and alumni support (over 2,000 signatures, in fact) to warrant an official response from the college administration. In an email sent on Aug. 31, the college president’s office regrettably stated that they were “unable to honor the request to rename Hasbrouck Dining Hall” due to the request’s inconsistency with “longstanding practice and current Board of Trustees.”

We at The New Paltz Oracle understand the bureaucratic difficulties of pursuing such a name change, but we also believe that there is a larger issue at hand regarding Hasbrouck Dining Hall. Its namesakes, Jean and Abraham Hasbrouck, Huguenots who founded New Paltz in the latter 1600s, were noted slave owners. And they weren’t the only slave owners to be immortalized on campus. A document from 1805, unearthed in 2001, lists other Huguenot settlers, “Bevier, […] DuBois, Deyo, LeFever [sic],” as slave-owning families that received public financial aid while caring for the freed children of their slaves, according to The Times Herald-Record. Readers may recognize some of these names as Bevier, DuBois, Deyo and LeFevre are all the names of residence halls comprising Hasbrouck Complex on the SUNY New Paltz campus.

The New Paltz of over three centuries ago is decidedly different from the New Paltz of today. Though the Huguenots were French Protestants seeking freedom from religious persecution, they did not extend that freedom to everyone in their settlement. For many at SUNY New Paltz, the names of their residence halls symbolize not founders, but tyrants and oppressors, and the continued use of these names only serves to glorify milestones achieved by white people standing on the backs of unpaid African slaves. What kind of message does this send to the black population on campus? That what they did for white people outweighs what they did to black people? That their contributions as wealthy slave owners are more significant than the forced contributions of the slaves themselves?

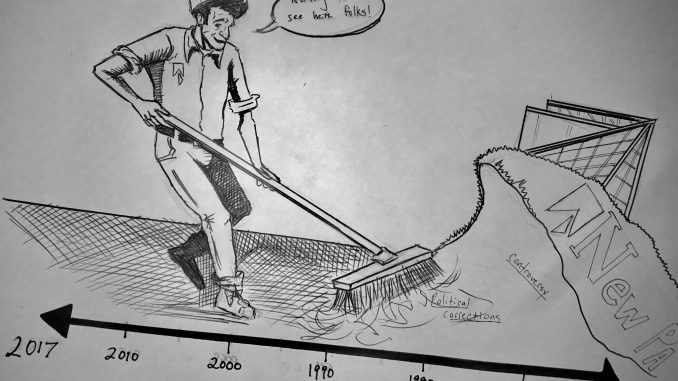

It’s even more troubling given the more widespread exposure of white nationalism as of late. Confederate statues and their propriety in a 21st century America are at the center of a nationwide debate, but to point the finger of blame squarely at the Confederacy for upholding slavery is to ignore the role this nation itself played in sustaining the institution. Before slavery was something the Confederate States of America fought to uphold, it was something our own United States upheld uniformly. If we are going to move forward, not only must we condemn historical figures who seceded to keep slavery, we must take responsibility for the sordid legacy of human bondage upon which this country was founded in the first place. That legacy includes the families Hasbrouck, Bevier, DuBois, Deyo, and Lefever and their complicity in its preservation.

An August 14 on statement from SUNY Chairman H. Carl McCall and Chancellor Nancy L. Zimpher claimed that “SUNY stands united against racism, violence, and intimidation” and that it “support[s] [its] underrepresented populations to the fullest extent.” Part of that support must include acknowledgment and condemnation of slave owners and their practices, regardless of their historical relevance to the area.

To the school’s credit, the president’s office has acknowledged the controversy surrounding the names of these buildings, assuring students of its intent to “ensure that the visible symbolism of building names is culturally consistent with [SUNY New Paltz’s] values.” Furthermore, the namesake of the campus library—former slave, iconic abolitionist and women’s rights activist Sojourner Truth—suggests that the school fully intends to foster an environment that recognizes all achievements, not just those of white European men at the expense of others.

We commend the school for taking the first step in addressing this issue by opening up a dialogue—so let this be a voice in that dialogue. In his 17 years working for Sodexo, Darold Thompson had more of a direct positive impact on SUNY New Paltz’s student body—people of all races, backgrounds, and ethnicities—than these slave-owning Huguenots from centuries ago. That is why we at The New Paltz Oracle believe that, in order to truly take steps to move forward from our ugly history, we must fully understand the difference between recognizing that ugly history and lionizing it.