Contrary to the mainstream belief that men were the only heroes fighting for America overseas during World War I (WWI), close studies conducted of fictional females have led experts to start thinking otherwise.

On Thursday, Feb. 28 Susan I. Lewis of SUNY New Paltz and Emily Hamilton-Honey of SUNY Canton hosted “Running the Gamut and Gauntlet: Mixed Messages in World War I Girls’ Series Fiction” in the Honors Center.

Part of the Women’s, Gender and Sexuality Studies Program Winter Colloquium, the presentation focused on the mixed messages that girls’ series transmitted to their young readers during the first world war.

This was a time period when women were attempting to forge new, more active roles on both the home-front and the battlefront, Lewis said.

Hamilton-Honey said prior to the war, isolationist adolescent publishers concentrated girls’ series fiction on female consumerism. During the Great War, publishers found it difficult to appeal to girls, but somehow had to get their female characters to support the war.

Hamilton-Honey said girls’ fiction series publishers of the time felt that “as long as you keep history out of it, the marketing opportunities are endless.”

“Girls weren’t taught to be active in war time. Series’ either put girls in the war zone and had the series end or had the girls return home for reasons related to home-life,” Hamilton-Honey said. “But these books are unique because by putting girls in the war zone, WWI dated the series.”

Some of the series’ Hamilton-Honey and Lewis mentioned were “The Khaki Girls,” “The Grace Harlow Survey,” “The Outdoor Girls” and “The Somewhere Series.”

Hamilton-Honey spoke about how actual professions of women in the war weren’t shown in fictional books about the war. Unlike the widespread idea that women started working men’s jobs in World War II, Hamilton-Honey’s presentation showed that in WWI women were also in the Navy and U.S. Marine Corps. Women worked as motor car and ambulance drivers, reporters, entertainers and telephone operators among other occupations.

“The Outdoor Girls” depicted women staying on the home-front working for the Young Women’s Christian Association (YWCA) as fundraisers and house institution hostesses. Patriotic propaganda about what women did surrounded the series and as Hamilton-Honey said, “what these books exclude is almost as interesting as what they include.”

The crux of many of the fictional girls’ goals and narratives was to serve their country out of a sense of duty or patriotism, Hamilton-Honey said.

Lewis’ portion of the presentation titled “Competent to Conflicted” mainly covered the heroines of “The Somewhere Series,” a series published between 1918 and 1919, in which each book is centered around a girl from the United States, Belgium, England, France, Italy and Canada.

“The girls are intimately connected with being involved in the war but are mostly concerned in being recognized for what they do,” Lewis said. “As the series progresses, increased narrative space between the heroines’ accomplishments can make you forget about their accomplishments completely. So then what’s the point?”

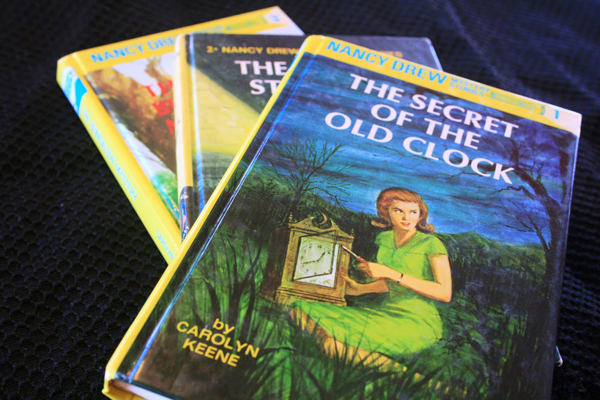

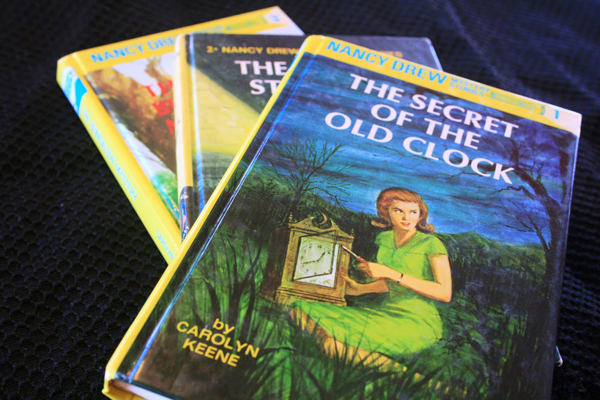

Arguing that WWI girls’ fiction series are more feminist than books that came later, Lewis pointed out how the “Nancy Drew” series doesn’t need to say “Nancy is a girl and can do anything a boy can do,” while WWI girls had to fight for this recognition.

Lewis said she believes this presentation showed the past isn’t as traditional as it’s typically imagined. Hamilton-Honey highlights that the discussion of women in combat on the battlefield isn’t one simply held during the last 10 years, but one held during the last 100.