On Monday Feb. 19, former SUNY New Paltz professor Susan Stessin-Cohn gave a presentation based on her research of slavery in the Hudson Valley at Elting Memorial Library.

Cohn is a SUNY New Paltz alum, where she got her master’s degree in anthropology and early childhood education. She began teaching at SUNY New Paltz and was soon asked to fill a hole in the social studies department. “I really didn’t know anything,” Cohn said. She began researching for her new position. After that, she was “totally hooked with local history.”

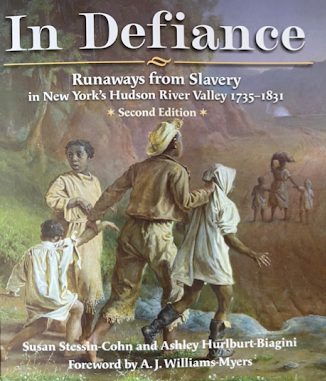

Cohn worked at Historic Huguenot Street and eventually threw her hat in the ring for the position of town historian. She is also the co-chair of the New Paltz Historical Society, and co-author of “In Defiance: Runaways from Slavery in New York’s Hudson River Valley,” which was published in 2016.

Cohn’s friend and mentor AJ Williams Myers was the chair of the Black Studies department, who influenced her main study of Black history in the Hudson Valley. Cohn soon realized it was a topic that many people do not know about with stories that needed to be shared. “I try to open people’s eyes to stories that they don’t know,” Cohn said.

Cohn’s presentation on Feb. 19 showcased the analysis of runaway slave notices and other historical records to gain insight into the lives of enslaved people in the Hudson Valley and depicted the arduous journey of African Americans in the area.

“Why do we use runaway slave notices to learn about people’s lives?” Cohn asked the audience. “I think it’s the most valuable source of information we can get.”

One slide in her presentation described how much information there is to analyze on a runaway slave notice. Her work underscores the significance of research and education in preserving local history and cultural heritage. “These people left nothing behind that is tangible that we could find out who they were, what their names were, what their life was like, and those notices give you bits and pieces of information. Yes, it’s through a white lens, but it’s a more honest lens than other pieces like for sale notices,” Cohn said. “Each notice is like a vignette.”

The notices do not define peoples’ lives, nor do they count as a single story for a human existence to be boiled down to. Cohn discussed how through each notice you can find a number of things like a person’s name, age, gender, complexion, height, weight, African scarification and languages spoken. Scars were telling as they could reveal both a person’s origins and how they were treated in enslavement.

Cohn came across one notice that became particularly important to her. It was of an enslaved man named Robin about eight or nine years ago in her research. She was able to follow a portion of his life through various notices and documents that she found, and learned that Robin was running from enslavement with a woman named Rose. The pair avoided capture for four years before they were apprehended. There is no evidence about what happened to Robin after that, but Cohn explained that being able to trace someone’s life for that long is rare.

“It’s amazing how much I found out about his life. It doesn’t happen that often, but it was like he was meant to be.” Cohn has gotten a glimpse into a myriad of lives — seeing them as not just historical evidence, but people that deserve awareness and justice. “I’ve spent so much time with them,” Cohn said.

Each untold story reveals horrific truths about humanity’s history. “This was their life, and this is what we have to learn about their life and how people treated other people,” Cohn said.

The demographic of Cohn’s talks and presentations is mainly older, white people, many of whom are fellow historians. Cohn explained she wishes more students would come to listen and learn about the topic she is passionate about — one that needs more recognition and awareness. Through teaching and discussing with her teacher friends, she has observed a common theme of students “not tuned in with history, especially local history.” The only way to address current social issues is by understanding the past, which was Cohn’s initial incentive — to educate students. “We have to see who we were and how we treated people,” Cohn said. “Part of this is for people to realize.”

Cohn and the co-author of “In Defiance: Runaways from Slavery in New York’s Hudson River Valley” Ashley Hurlburt-Biagini started collecting runaway slave notices over 20 years ago. They became friends and colleagues working at Huguenot Street. They started talking about their findings, and Cohn realized she had collected hundreds and hundreds of runaway notices. The first person Cohn approached was a publisher from Black Dome Press, who immediately took them on.

“In Defiance” documents 512 notices from archival newspapers for 607 slavery fugitives from 1735-1831 in the Hudson Valley. Cohn and Biagini spent a lot of time on the index in the back of the book, where each enslaved persons’ name is written along with information about their lives that would not get displayed anywhere else. Information such as who was a flute player, who was a carpenter and who spoke three languages. “Each one of these people — their lives counted, and I want people to see that,” Cohn said. In the future, she hopes to be able to produce a pathway in New Paltz with the names included in the book.

Cohn is excited for her upcoming talk on April 20 at Hyde Park’s Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum, as well as her current project: the Ulster County Truth and Reconciliation Commission, which she is presenting on June 2. This will display three years of research from Cohn and her colleagues.

Cohn’s current and future works serve to look back at our country’s past in order to “understand who we are as people now.”