The most common (and personally infuriating) trope in young adult fiction is found in the “first time” sex narratives. It’s no secret that the immediate reaction to that first time has always been to shame.

Up until the publication of Judy Blume’s “Forever” there hadn’t really been a story that discussed a couple engaging in sexy times without dire consequences (pregnancy, death, sent away to a convent, etc). The overwhelming argument underneath these stories is “don’t have sex: you will get pregnant and die.” To me, it’s archaic and exhausting.

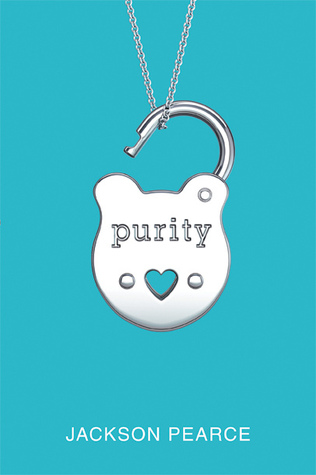

When I picked up Jackson Pearce’s “Purity,” I knew I would be getting into a story that challenged the trope. Yet, I still wasn’t expecting it to go so in depth into the issues of bodily autonomy.

The story follows Shelby, a girl who promised on her mother’s deathbed that she would “listen to her father, to love as much as possible and to live without restraint.”

This promise is something the character really takes to heart in just about every decision she makes, including when her father begins planning a “purity ball” — an event where girls pledge to “stay pure” at a formal dance. Not wanting to break one of her mother’s rules, Shelby agrees to take part, but she has her reservations and concerns with the whole idea of purity.

She decides the loophole to the whole purity promise would be to just go ahead and find someone to have sex with to “get it over with” and the events that follow are a bit slap-stick, following the very realistic awkward fumbling of sexual discovery. I appreciate the light-hearted approach because it is such a departure from the traditional “high stakes” mentality associated with sex. Keeping it light cements the idea that the value of a person really does not rest between his or her legs.

Ultimately, Shelby’s inner monologue starts to work out what the idea of “purity” means to her, but Pearce manages to make this social analysis less didactic — which for me, made it significantly less painful — by highlighting Shelby’s own uncertainty.

While the character values her bodily autonomy and finds her own issues with church-bred shaming of sexuality, she has a hard time putting those thoughts into words and an even harder time expressing them.

It’s this kind of real thought process that makes the novel work for me. There’s rarely anything to be decisive about when you’re young and that experience, frustrating as it is, is a narrative worth following.