On an Autumn day in California, after a Chinese gang missed their target and mistakenly killed a white man, a massacre ensued. Over 500 white and Latinx people surrounded the Chinese district in Los Angeles ready to kill in revenge. 17 Chinese people were lynched across the district, their bodies hanged in front of homes across the neighborhood. Nobody served time for these cruel, publicly executed murders.

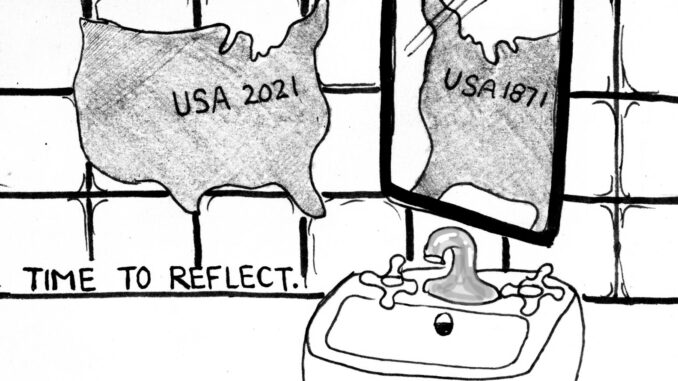

This massacre was in 1871. It happened just before the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 when Chinese people were banned from America for 60 years to maintain white purity. It also wasn’t long before the Rocks Springs Massacre, when about 130 white people attacked hundreds of Chinese mineworkers, murdering 28.

We also can’t forget when the Bubonic plague was incorrectly blamed on the Asian community in San Francisco, leading to hateful sentiments and violence, including police violence — not much different than the reaction to today’s COVID-19 pandemic.

Yet, even after an extensive history of anti-Asian violence in America, many non-Asian people appear to believe that this year our nation has experienced its first ever anti-Asian racism.

Last week, a white man entered a spa and murdered eight people, six of whom were Asian women. He said he did it to end his sexual fantasies, leading to widespread public outcry about the hypersexualization, fetishization and brutality against Asian women recently; Especially as it comes amidst a pattern of anti-Asian hate crimes that have steadily risen since the start of the pandemic.

According to Stop AAPI Hate, there were 3,800 anti-Asian hate crimes since March of 2020. (A number presumed to be underreported.) This is a 150% increase from the number in March of 2019.

There has been a clear and documented rise in violence towards the AAPI community since the beginning of the pandemic, partially thanks to powerful leaders such as former President Donald Trump blaming China for the virus and using rhetoric such as the “China-virus” and “Kung flu.”

Trump’s rhetoric, which was directed against by many — including the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) — had a direct correlation to the rise in violence against Asian Americans since the start of the pandemic. The United Nations Human Rights Council published a document arguing that Trump’s rhetoric “legitimized” the attacks.

In May of 2020, ABC News found that 54 hate crimes included the abuser invoking Trump’s name before inciting violence. The impact of Trump’s rhetoric and policy will last beyond his reign as president.

As the Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) community lives through an intense period of grief, mourning and fear, we stand by them. We recognize the intensity of their current grief while also honoring the grief within their full histories.

We at the New Paltz Oracle encourage the non-Asian community to actively stand in allyship with the AAPI community. Active allyship includes comprehensive education, which means examining the history of anti-Asian violence in addition to the modern experience of Asians and Pacific Islanders in America.

It’s hard to discuss violence targeted at AAPI people without talking about the ways anti-Asian sentiments live in many communities.

This hate isn’t only a white vs. Asian issue. Many communities of different ethnicities, races, genders, socioeconomic statuses and sexual orientations must hold conversations about the anti-Asian sentiments in their communities. But many history and sociology experts say it all boils down to the same issue: the structure of white supremacy.

“It’s not that Asian-Black tensions or racial hierarchies don’t exist today but that there is a failure to remember what got America to this place: white supremacy,” Vox published in an article.

White supremacy doesn’t dictate that whiteness is equally superior to all other races. It goes further, creating a hierarchy that divides people of color amongst themselves and creates animosity between them, which is referred to as racial triangulation.

An example of this is the “model minority” label, where Asian people were stereotyped as the ideal immigrant: hard-working, obedient, quiet. Illusions of complete financial security within the Asian community were used to shame other people of color for not being where they were and to erase the voices and experiences of AAPI people.

Of course, this isolated groups from each other to distract them from the common enemy.

To dismantle the structure of white supremacy, people of all ethnicities must unite, which would help shatter the structure of dominance and triangulation.

As a result of a common enemy, it is in each person’s best interest to join together with the Asian community to rally and organize against the system of white supremacy. An example of this can be seen in the 1969 Third World Liberation Front Movement, where students of several backgrounds came together to successfully advocate for curriculums to include not just white history, but also Black history, Asian history, Chicano history and Native American history.

“This solidarity has been happening for a long time. Black folks have been showing up for us, Latinx folks have been showing up for us, all other communities have been showing up for us,” said Michelle Kim, activist and CEO/co-founder of Vision Awaken, which empowers leaders to lead inclusively. “We just don’t know because media has a vested interest in hiding these stories and… [us] fighting in silos.”

In an Instagram live, Kim also cautioned against thinking about allyship in a way that is “transactional.” She’s attested to hearing many people saying “I was rooting for Black Lives Matter, where are theBlack people now?” She validated where it’s coming from and the pain of erasure, but did offer another way of thinking.

“We don’t show up to Black Lives Matter marches so that other people will show up for us … or because we want something in return. [When] we show up for Black people we are also showing up for us because the root of that oppression, is the same as our oppression,” she says.

As awareness of the AAPI experience continues to spread, people must continue to take note of what was successful during this summer’s Black Lives Matter movement and what was not. The collective history of battles against white supremacy are all relevant, but each soldier must take note of what went right and wrong in previous battles for the army to gain strength together for the continued progress of future battles.

This summer we learned that black squares, just like yellow squares, do little to nothing to combat racism. But we also learned that petitions, widespread public outcry and thousands of phone calls do interrupt the system of white supremacy. We learned that while “End racism!” posts may not do much, sharing information and resources do.

We learned that performative activism and temporary attention does not help; ongoing support is what makes lasting changes.

We at The Oracle urge each person to recognize the struggle and mourning of the AAPI community right now as something that must be acted upon by all, as the eradication of anti-Asian violence is something that benefits everyone.

Within our lifetimes, this may be one of the most urgent times to act, both nationally and locally. While it may be easier to put all the blame on violent people far away, we must analyze the ways that we have been complacent in our own lives.

It is not enough to not be racist, you must be anti-racist.

In New York City, seven Asian people were violently attacked in hate crimes over just this weekend. This editorial is dedicated to them and those who were killed in the spa shootings last week. (Some of whose families do not want names to be published.)

If you’d like to stand with the AAPI community, the following are organizations to check out and consider donating to or volunteering with: Red Canary Song, ButterflySW.org (which both focus on Asian, migrant sex workers in NYC); Womankind (formerly known as New York Asian Women’s Center, works with Asian survivors of gender based violence); Makong NYC (works with the Southeast Asian community in the Bronx and NYC).