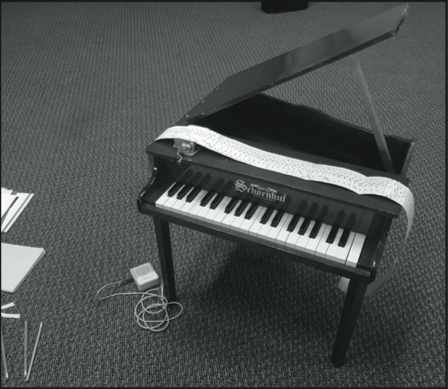

Pianist Phyllis Chen ran an experimental music workshop on campus, showcasing her musical instrument of choice: the toy piano, a smaller version of the traditional piano with a smaller musical range.

Chen is the current Davenport Artist-in-Residence at SUNY New Paltz. A classically-trained pianist who began playing at the age of five, the musician is well-regarded among her peers.

Many people first encounter the toy piano in their youth. But Chen did not come across a toy piano until her 20s, when she heard one played at a puppet theater and fell in love with the whimsical sound. Since then, Chen dedicated much of her time and practice to composing and playing music on the tiny instrument. The musician is now regarded as a world-renowned toy pianist and she’s extended her passion for toy pianos to others. Chen founded UnCaged Toy Piano, an annual composition contest and festival celebrating the instrument.

Over 50 students, faculty and guests met in the Shepard Recital Hall on Wednesday, Oct. 7 to learn and hear Chen play. Sitting cross-legged in front of her apple-red toy piano, Chen opened the workshop with “Carousels,” an original composition for both the toy piano and a wind-up music box. Chen said she purchased the paper for the music box in Germany. The resourceful musician used both sides of the paper in her composition, punching holes for half of the song on one side and the remaining half on the other.

True to Chen’s word, the instrument gave off a magical, whimsical sound. The composition was masterfully layered and absolutely beautiful to hear. Chen played her toy piano with elegance and grace and as the song faded out, the audience remained still, enchanted by Chen’s composition.

The pianist used “Carousels” as a starting point to discuss influential American experimental and avant-garde musicians. She played a variety of songs, including pianist John Cage’s famous song “4’33”,” alternatively known as the silent piece. Cage coined the term experimental music. Unlike his peers, Chen said, Cage was not concerned with meaning or feeling; he wanted to know what made music, music. To play the song, Chen needed an audience member to sit silently with her beside a traditional piece for exactly four minutes and 33 seconds.

“Anyone want to do this with me?” she asked, and was promptly greeted with silence. “No?”

The audience chuckled. Afterward, Chen’s reluctant audience volunteer expressed his discomfort during those four minutes and 33 seconds. Chen herself agreed that the piece was uncomfortable, both from the musician and the audience member’s point of view.

“The [noise from the] environment is put on stage for us to hear,” Chen said about the song. “I’m much less comfortable with silence. I’d rather be playing.”

After another experimental song, Chen invited her audience to participate in musician Pauline Oliveros’ Sonic Meditations. The Meditations are designed to make participants hyper-aware of all noise and sounds around them, Chen explained. Since many of the pieces only involve using one’s body to make sound, anyone can and should participate; Oliveros designed these pieces as a “tuning of the mind and body.”

“Music is just a byproduct,” Chen said.

One Meditation involved attendees repeating noises they were forbidden to make during childhood. Another called for attendees to walk around the room and “fish for sound,” a request Chen described as catching a sound and repeating it back to the group. Participants took Chen’s request to heart, flooding the recital hall with a cacophony of humming and strange sounds.

Chen also played “Nothing Is Real,” a unique composition by experimental musician Alvin Lucier. To perform “Nothing Is Real,” Chen played the melody of The Beatles’ “Strawberry Fields Forever” on a traditional piano, recorded it, and played the recording back through a teapot afterward. The specific teapot was a hot topic of debate between Chen and her mentor, who sampled the piece through teapot after teapot to find the one with the perfect sound. Their ideal teapot came from a random market in New York City’s Chinatown.

At the end of her workshop, Chen opened up about her passion for the toy piano. She shared details about her quest to find old toy pianos on Ebay, since contemporary toy pianos are not made with the same degree of craftsmanship as older models, she said. Many of these older toy pianos come with their own unique flaws and blemishes, but these random, low-tech qualities are part of the toy piano’s appeal.