In ultra-Orthodox Jewish communities, the terms “sexual abuse” and “sexual assault” are forbidden.

However, the topic was deeply discussed during Judy Brown’s visit to SUNY New Paltz on Sept. 14. Unfortunately, in the deeply religious world in which she grew up, child molestation runs rampant.

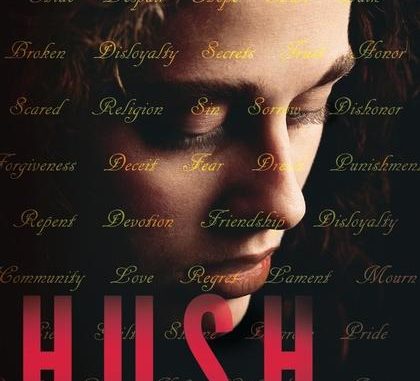

Brown is a woman who left her Hasidic community in Brooklyn after writing “Hush,” a fiction novel based on true experiences of sexual abuse and suicide written from the perspective of a child. The writer was burdened with stories of suffering from those whom she referred to as “the children of the underworld.” Among them was a young girl expelled from school for reporting molestation.

She began releasing these stories onto the page as a form of therapy after her peers confided in her about horrific sexual abuse they had endured. But Brown said writing the novel “quickly became a nightmare.”

In 2010, she published “Hush” under a pseudonym, Eishes Chayil, out of guilt for carrying these harsh truths with her. Brown received major backlash from the community when she revealed her identity in a Huffington Post article in 2011.

“Writing wasn’t a gift; it was a betrayal. It violated the rules of what you are not allowed to know,” she said of the Hasidic community.

Being ignorant of the repercussions of leaving, wanting a better life for her children and feeling shunned by her community, Brown felt she had no choice but to leave.

“I don’t encourage women to [leave like I did]. Some don’t survive it,” she said.

Brown spoke in front of a packed Lecture Center Room 104 as part of the Resnick Lecture series, “Jews and Modern Memoir.” She was the second speaker in the series, following a man, Shulem Deen, who also spoke about leaving the Hasidic world.

“It is a coincidence that the first three speakers are people who have left the world of ultra-orthodox Judaism,” series director and emeritus professor, Gerald Sorin said.

Sorin chose Brown to speak at New Paltz because he was very impressed by her novel, and found it important for others to engage with her on it.

“[The series is about] people learning about other people’s lives and culture, and people who have made very consequent changes in their lives,” he said. “It’s important to hear that.”

Brown is a survivor. She wrote a heart-wrenching novel, faced threats from the community that raised her, won custody of her children and now continues to speak about it at lectures such as this one. But as far as she is concerned, her experiences have not made her stronger.

“I don’t buy into that,” she said. “I appreciate the person I am but I am broken.”

She explained that it is very difficult for women to leave the Hasidic world. They live under a “dome” for 20 years, get married and often have two or three children by the time they are in their early 20s. Leaving alone is one thing, but leaving with your three children is another.

Brown left when she was 30 years old and spent three years “battling for her life.” Although her children are better off now, she is traumatized by a past of living in poverty, having tensions with her family, fighting a custody battle for her children and ultimately, for her life.

“In the Hasidic community, children are seen as community property,” she said. “It took me several years, and you’re always still a little tangled in it.”

An in-depth Q&A followed Brown’s solemn, forthright speech about how “Hush” came to be. The conversation focused on the cultural implications that allow such horrific and widespread sexual abuse to continue in this religious community.

Brown’s message was that change must come from within and is doubtful, going by the utter lack of changes in the community to this day.

Many attendees wanted to know what the secular world has done to help. Brown pointed to an organization called Footsteps that, according to their website, “provides a range of services, including social and emotional support, educational and vocational guidance, workshops and social activities, and access to resources” for those entering the secular world from ultra-Orthodox communities.

“I was barely scratching through [leaving and being in poverty] but I was lucky in little ways,” Brown said. “On the other side, I’m happy I did it. My children are different kinds of people so it paid off, but I don’t think I’ll get over it. You recover for the rest of your days.”