Content Warning: The following article discusses the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on hospitals and their employees, and includes mention of heavy topics such as death and illness.

When I was much younger, my dad mentioned to me that when he was in high school, he came very close to joining the military. The thought of my dad enlisting terrified me because I imagined his safety being compromised again and again with each passing day.

Today, as my dad works as a respiratory therapist in a high-risk COVID-19 unit, my family and I live with a fear similar to the one I had envisioned when I was so young. Except now, he heads into combat wearing scrubs instead of camouflage.

Before this year my dad, Mark Spence, had worked as a respiratory therapist at Lincoln Hospital for 27 years, and served on the management team since 2012. This career was already no easy task, demanding frequent 12-hour shifts of focus, precision and compassion.

But today’s global pandemic has wreaked havoc on the healthcare community, especially for respiratory therapists. Overnight, everyone’s workloads tripled, and the number of deaths per day skyrocketed.

“As a respiratory therapist, or as any healthcare worker, we look around us and see the amount of people dying, we look around and see the amount of body bags,” he described with a distinctive sense of pain woven through valor. “This has to be one of the most painful experiences for any healthcare worker living today.”

The dramatic shift has taken a huge emotional and physical toll on healthcare workers. On a daily basis, they’re surrounded by panic and death, faced with 12-hour shifts that commonly drone into 14 and 15 hours. On top of this, healthcare professionals are also at increased risk for being seriously impacted by the virus.

My dad says he doesn’t mind working longer hours for such an important cause, and is prepared to be there for additional time if they need him. But the emotional pain is something you can’t prepare for.

“It’s the most disheartening, difficult, emotionally draining and, at times, hopeless thing. Sometimes there’s a level of hopelessness. This is our trauma,” he explained thoughtfully. “I will go to therapy now. A lot of us will.”

Possibly because he senses the devastation and worry in my voice, he shares a more uplifting sentiment: Every couple of hours, he tells me, applause rings over the speakers to honor the recovery of a patient whose initial prospects of being discharged from the hospital seemed unlikely.

“We have a lot of success stories,” he said. He recalls the utter joy in the hospital when one of his coworkers who had a history of asthma recovered from COVID-19 and was able to go home and be reunited with family that she’d believed she would never see again.

“The sad part of this is knowing you’re dying and you will never see your son, your daughter, your brother, your cousin — you’ll be alone,” he offered in regards to the nationwide policy preventing loved ones from visiting COVID-19 patients in hospitals and other healthcare facilities.

Another aspect of the sadness and frustration he faces while working in Lincoln is seeing firsthand that something is being ignored on a wide scale: “It goes back to the sad fact that poor people are always at the disadvantage.”

Lincoln Hospital is located in the South Bronx, which is the poorest congressional district in the entire country and, not coincidentally, is in the borough with the highest rate of COVID-19 deaths.

“No matter how you cut it, it always ends up being the voiceless, the impoverished, the disenfranchised people who will suffer more, and the COVID-19 virus is no different. It’s straight-up socioeconomics,” he said.

For example, the barrage of fast-food restaurants and liquor stores in low-income neighborhoods primarily sell products that exacerbate conditions like diabetes and liver failure, respectively. These are both conditions found to cause a higher risk of more severe COVID-19 complications.

An even more blatant sign that the Bronx would experience so many fatalities is that those with asthma are at high risk for complications from COVID-19, impacting many Bronx residents. The borough has the highest incidence rates of asthma in the country, with hospitalizations for asthma in the borough rising 21% above the national average.

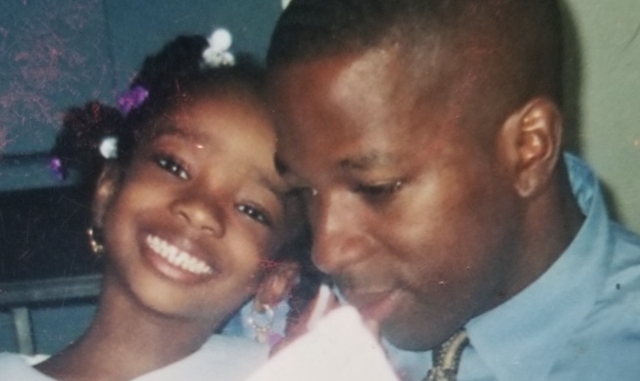

For those who know my dad, it’s no surprise that he would be especially wary of the social justice implications of the virus, as well as ignited with inspiration to help the communities it would impact the most. He has taught me since I was young that my focus in activism should begin with healing my own communities and heritage, especially because we have so much to get done. The Bronx was once my family’s home and in my dad’s heart, it’ll always be a place that we are obliged to serve.

In fact, he feels that working exactly where he is right now is what he was meant to do.

“It’s frightening, it’s scary, but you do it because it’s your calling,” he reflected. “This is my calling, so it comes natural to me, and I wouldn’t want to be doing anything else right now.”

It’s terrifying to see a man I love so greatly — who taught me everything I know about leadership, courage and integrity — head into such a gruesome environment every single day. But watching him do so fearlessly, yet with such arduous passion, exemplifies everything he’s ever taught me.