While navigating through college, many people tend to consider stress to be a given. Instead of having short periods of high-stress surrounding important dates or deadlines, we seem to exist in a perpetual state of stress, trudging through these four years as balls of tension.

Stress has become just as much a part of the quintessential college experience as things like frat parties and midnight pizza. Even worse, it has no discernable end — stress follows you from your freshman year, desperately trying to get acquainted, right up to walking at graduation, post-undergrad plans lurking in the back of your head.

For most, this stems from the expectation to always be “on,” or a pressure to be constantly performing. It’s common knowledge that during college, a lot gets thrown on your plate, often much more than anyone could handle. There’s classes and the demand to perform well in them. There’s extracurriculars, some done for fun, but most done with the future in mind. “Will this look good on a resume?” often matters more than enjoyment. On top of all these responsibilities surrounding school, there’s work and, eventually, finding a steady job.

These packed schedules are enough to send anyone straight to their breaking point. They’re likely to blame for the fact that 85% of college students reported feeling overwhelmed with their responsibilities, according to the Anxiety and Depression Association of America. In the same study, it was reported that 30% of college students felt that “stress had negatively affected their academic performance.”

At The New Paltz Oracle, we recognize this as a clear and present problem, and one that should be routinely monitored and addressed by those in academic leadership positions. We hope to see more being done to change the belief that stress and college are a package deal, both culturally and here at New Paltz.

There is obviously no magic switch that can turn off stress in all college students, because despite the common factors shared by this demographic, stress still presents itself in different ways to each individual person. Still, there is plenty that can be done (and said) to alleviate the pressure placed on students.

At New Paltz, professors decide what, if any, effect attendance will have on final grades for each of their classes. Most commonly, students are allotted two to three absences — any more after that and you are placed in danger of failing the course, many syllabi warn.

Of course, these strict policies aren’t put in place to hurt students. The hope is that by requiring attendance, students will be encouraged to be present and avoid falling behind. However, a physical presence in class doesn’t always mean that the student is checked in mentally.

With only two opportunities to miss class without impacting their grade, students end up feeling discouraged against taking days to themselves. They drag themselves to class with a cold so that they can stay in bed if they ever get the flu; they avoid taking mental health days to reserve the freebie for more socially acceptable emergencies. When they do miss class, they stress about missing class; this causes a self-destructive cycle that is hard to escape.

Some professors will excuse an absence if a doctor’s note is presented, but this also places pressure on students. Not all illnesses require a visit to the doctor; if you are suffering from a cold, for example, you may not deem it necessary to drag yourself out of bed and to a doctor or the campus health center, which is understandable. So why must we prove that we were sick, and why does there always need to be an excuse?

Most college students are over the age of 18, with many being in their early twenties, and nearly all pay for their education in some way. Thus, the responsibility of being present in class should fall on the student and the student alone. There should not be strict standards that lead to stricter punishments. If an individual decides to skip a majority of their classes, then it is likely they will not perform well. Why then punish a student with a chronic illness, for example, for missing class due to circumstances beyond their control?

We at The Oracle believe that penalizing students for their absences is not only unnecessary, but harmful. The difference between a student who skips class just to skip class versus one who truly must is often an obvious one, and forcing the latter’s grades to suffer due to unforeseeable circumstances is frankly unfair.

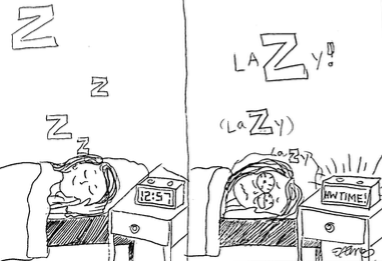

This all goes back to the idea of constantly being expected to perform. In college and our society as a whole, rest is looked down upon. If you aren’t up past midnight doing work, you’re not trying hard enough, but if you don’t wake up before 9 a.m. the next morning, you’re lazy. It’s an endless cycle, and one that no one can healthily master.

In other cultures, rest is valued. For example, in countries like Spain, it is common for offices and schools to honor a “siesta,” a nap or period of rest taken in the afternoon. This hour or so of rest is cherished in some cultures for its ability to rejuvenate an individual at the midpoint of the day. In America, a siesta would be a sign of laziness.

Our culture views sleep deprivation as honorable, while rest and self care are luxuries. Instead of mental health care being ingrained into our schedules, we are forced to decide whether or not we want to sacrifice an allotted class absence for a dire mental health break.

Capitalism plays a big role in why our culture considers rest to be dishonorable. There’s a common saying that Americans live to work, while Europeans work to live, and it couldn’t be more true. We are raised on values of hard work from the minute we wake up to the second we fall asleep. There is also an enormous emphasis on blaming the individual in a capitalist society. If you don’t get a job, it’s your fault; if you need a day off, there must be something wrong with you.

We hope to see a day where our society embraces rest as a necessity rather than a luxury. Until then, we ask that more is done to ease the pressure of always being “on.” The world won’t end if we take a break.