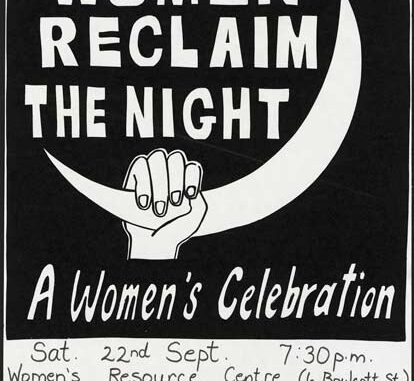

This weekend I had a (virtual) conversation with Kaitlyn Gonzalez, President of the New Paltz chapter of Take Back the Night (TBTN). TBTN is an international organization working to combat sexual assault and domestic violence. It was named after the annual march, which was born in the 1960s in England. Women came together, marching and chanting fiercely, to not only raise awareness but also to create for themselves a sense of power and safety at night, something stolen from many women. Today, the march happens annually in 30+ countries.

The graduating third-year biology student has been a member of the organization since she arrived in New Paltz from Long Island in 2019. She became president around the time that everything shifted online, meaning her leadership has had its own unique set of challenges.

Still, the future medical student has continued to move the club forward effectively, just on a bit of a different path. “Our format changed from a lot of community outreach, orientations and in-person events, to now where we do a lot to build community within our members,” says Gonzalez.

Community-building is a paramount goal of the club this year, which is timely given that forging bonds and surrounding oneself in a supportive community has been harder than ever thanks to the social distancing and isolation that has become the norm during the pandemic.

Within a few minutes of meeting Gonzalez it seemed clear that if anyone could successfully take on such a difficult goal — fostering a tight-knit group and creating a safe space virtually to talk about such heavy and personal topics — she had the qualities for it. Her presence is gentle and warm, plus wise and knowledgeable; she’s someone you immediately trust.

Amayah Spence: How would you describe the TBTN community on campus?

Kaitlyn Gonzalez: Empowering and supportive. You walk into a space where you immediately feel safe. And people might not know your story — no one’s ever pushed to tell their story. And you don’t have to have a story, you could just be an ally.

But you walk in knowing that that’s understood, that no one judges you and that whatever your story may be, everyone in that room believes you.

Building that community, especially in a public place, is super important because these topics mean a lot to people — whether you’re a survivor or an ally — so you want to feel like you are in a space that makes you feel empowered and safe so that if something triggers you or was a little heavy you feel comfortable reaching out and saying ‘hey, this was a little heavy for me. Can anyone help me out or provide me with some support?’

AS: Is there a particular program or experience with the club that you’re still thinking about to this day?

KG: We had one program called “Masks & Trauma.” With the pandemic everybody’s wearing masks now and that can be hard for survivors: just the thought of wearing a mask can be triggering in some ways. I never even imagined that it could’ve been an issue. I’m stepping out of this with a whole different perspective, because right now we’re in a world where you see someone without a mask and you think, ‘Oh you don’t care about other people’s health.’ But it could very well be that they have their own stuff going on and in that moment were feeling triggered and they had to take a moment to unmask themselves. I think everybody at the program was like, ‘I’m walking out of this feeling so much less judgmental towards people because I don’t know their story, and looking at it in a way that I’ve never looked at it before.’ I liked being able to provide that for them, that was really empowering.

AS: How might face masks trigger survivors?

KG: There’s a lot of different people who can be triggered by masks, not just survivors. There’s also people who have claustrophobia; there’s something called gas mask-phobia that’s a blanket term to describe the whole thing, and it’s the feeling of when your face is covered and you have a little bit more difficulty breathing and that almost triggers an anxiety attack [because] it triggers your fight or flight — that nervous system reaction.

It’s not your fault or that person’s fault. Your body is literally just trying to warn you that something is off.

The mask can bring back memories of an instance where there may have been something covering someone’s face, and there may be an uncomfortable association. We also talked about ways to remedy that […continued on website].

AS: What will the Take Back the Night annual event be like this year? Will the annual march go on?

KG: Usually, every year we host a big Take Back the Night event that is a day-long thing during sexual assault awareness month [April]. A ton of different speakers come out and it’s usually ended off with a march. So we have kept up with the [march] but it’s become a bigger day of empowerment and education.

This year things are a little different with COVID-19. We’re still going to have our big event. It’s just going to be online.

[Maybe we can do] a socially distanced walk at the end of April.

AS: What are the biggest differences in how you navigate the world before and after being part of TBTN?

KG: We didn’t have anything like this in my high school. It was a thing nobody really ever talked about unless you talked about it with a close friend.

As an individual, I found that before having this space to talk, I internalized things so, so much. You hear all these messages or events that may happen and you internalize that and you don’t have anyone to talk about it and say, ‘that’s not okay.’ Or, ‘I believe you,’ or anything like that.

When there’s no space, I found myself in situations where I didn’t understand that what was going on wasn’t okay. And that’s why I feel very strongly that these things need to be talked about because sometimes you find yourself questioning your own self. So to have a space where [you’re reminded]: ‘Your feelings are valid.’ and ‘No, you’re not just overthinking,’ and ‘It’s not you, you didn’t do anything wrong in this situation,’ is extremely, extremely empowering. And really, really helpful for mental health.

I think as a community, when you don’t have a space like that to talk, it kind of upholds this whole atmosphere where things aren’t really being discussed and just go under the rug. [An atmosphere where] things happen and everyone’s kind of hush about it. And people are so much less likely to reach out for help if they feel like there’s no space for them to be heard.

AS: What are some things you’ll be taking with you after you graduate both from the school and the NP chapter of TBTN?

KG: All the knowledge that I’ve gained, both in self-care and grounding but also in knowing how to be a support for others. Knowing when to speak up, and how to go about speaking up. Knowing what my rights are.

AS: You mentioned learning good ways to support others. Do you have advice on how allies can support survivors?

KG: I think the biggest thing is just unconditional love and support. You may not understand what they’re going through, you may not have ever been through it and that’s okay. They’re not expecting you to understand it, they would never want you to have gone through it and to understand it. You don’t have to ask any questions, you don’t have to say the right thing. You just have to be there and let them know: ‘You are validated. Your experiences are valid. I believe you. What can I do to help you?’

Let the control and power be in their hands. I think the biggest thing for survivors is that feeling like you’ve lost control. So even when reaching out for help if you go to someone and they start asking a bunch of questions about specifics, or pushing you to do a certain resource whether that’s reporting or reaching out. If you’re ever unsure, put that control back in their hands.

‘What do you need from me? I can help in any way that you need. If you want to report, I’m there for you. If you need someone to listen, I’m here. Whatever you need, I can do that. Your experiences are valid and we don’t have to talk about it at all if you don’t want to. That’s your right and that’s your power.’

AS: Do you have advice for survivors navigating Sexual Assault Awareness Month on social media where well-intentioned posts to raise awareness can often be triggering?

I find that this happens, not just with survivors but in other instances and other problems out there too, where in educating and trying to put out information for people, it ends up not being accessible for the people who are affected by it. It’s not on the survivor to not be triggered, it’s up to those who are trying to uplift their voices to take a step back and think, when I share this, what’s my purpose in doing this? Who is it for? Is this something that’s not even going to be accessible for the person that I’m trying to uplift?

Personally, I find that taking a break from social media, especially in these times where everyone’s reposting and putting out information — and everyone’s just trying their best they’re all just trying to get information out there but that can be a lot. When you’re dealing with these experiences every day, and now you’re coming into a month where most people are just kind of starting to talk about this for this month, that can be super overwhelming.

AS: What are your hopes for the future of this club?

KG: One, that it doesn’t die out because it’s a really important club on campus. Two, I want to see the club grow, especially in terms of intersectionality and making sure that everyone feels heard and represented. And I think that’s a big thing: recognizing that people’s cultures and backgrounds really affect their experiences too, and their experiences cannot be compared.

AS: That’s true and yet there has still been so much jargon recently about how “Everyone is going through the same thing” and other cliches to that effect. But contrasting that, can you think of an example of how someone’s background, culture or lifestyle may impact their experiences, specifically with sexual assault?

KG: I try to look at it from a personal point of view. I’m Puerto Rican. I went to a talk a few years ago and the term they used was machismo, to describe the male is the head of the house kind of thing. So if you’re coming from a culture like this where men are very, very heavily upheld and you’re trying to speak out about an experience that you have, your experience in even just speaking out, is going to be completely different than coming from a culture where it’s equal or there’s no difference there.

Also, people will say you can report to police, and yeah, they’re there, but that’s coming from a privileged standpoint: you feel comfortable doing that and that’s a space that you’re going to be listened to and heard. So you cannot say, ‘Well I went to the police and they said this’ to tell someone else who is a person of color that they can do the same thing, because coming into that experience is a completely different ballgame. [It’s about] recognizing that there are these differences where you just can’t compare, and every person’s experiences change their story and the way they’re going to react to things and that’s okay.

We just need to be open to understanding that and letting that person take the wheel, not trying to tell them how they need to take the wheel.

AS: How do you create safe, intersectional spaces where inclusivity is emphasized?

KG: It’s a space where one, you see yourself represented. When you come into a space and there are other people who look like you and you have similar cultures and backgrounds, you immediately feel like, ‘okay, they might understand. My experiences are shaped by my culture and they may understand why I feel that way because they share that too.’

Another thing that also makes it feel intersectional is that [these topics] are actually spoken about and it’s recognized that supporting BIPOC survivors and supporting LGBTQ survivors is completely different than supporting cis survivors and white survivors. And there’s nothing wrong with it, we’re supporting everyone, but it’s completely different. So coming into a space seeing that that’s being addressed.

For International Women’s day we specifically focused on Black women who had made strides in women’s rights and feminism and something that stuck out to me was that the me too movement was very big but that phrase had been started by a Black woman [Tarana Burke] many many years before it became a platform on Twitter. She had coined that to help people, it was her life’s work. And then it blew up on Twitter when a white woman used it as a hashtag. This is someone who has been spending her whole life working in this field empowering others and uplifting survivors and wasn’t really heard until someone else took it. There’s so much work to do in terms of knocking down those walls to make everyone feels safe and the basis of the movement is diverse and you are represented in the spaces of the movement.

Take Back the Night meetings are Mondays at 6 p.m. on Zoom (link can be found on their Engage page). Upcoming events include a virtual viewing and discussion of the film Moxie with digital media studies professor Megan Sperry on April 14, an online paint and sip on April 13 and other events.