I first read David Foster Wallace’s “Infinite Jest” in the summer after my junior year of high school. It was about a year after his suicide and I’d spent the long days lifeguarding and flipping back and forth between the pages of the massive book. During my senior year of high school I carried around my well-loved copy of “Consider the Lobster,” re-reading the same words until the pages were frayed and decorated with coffee stains.

My Wallace books became special to me; his words reminded me of the power of attention, the dangers of solipsism and just how difficult it really is to be moral.

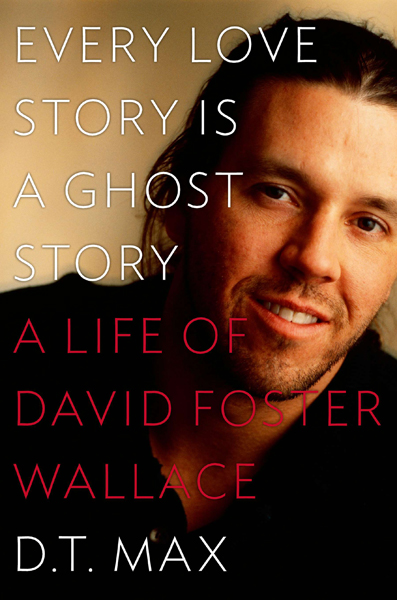

So when I picked up “Every Love Story is a Ghost Story: A Life of David Foster Wallace,” D.T. Max’s biography of the man behind those words, I was worried. I wasn’t the sort of megafan who felt the need to force my moral ideals on the author. I understood that there’s a separation between a writer and his words, but I couldn’t escape those warnings from friends that the real Wallace was too unlikeable and that the way I read his other works would change.

In a way, they were right.

Max is respectful in his portrayal of the late author without being overly reverent. His thorough use of his friends, family and different letters as sources allows a glimpse into Wallace’s head. There’s a bit of complex in Wallace — that need to be the smartest or the best — that clouds a lot of his action. He’s difficult, rude and competitive and, ultimately, just as anxiety-prone as his prose would lead you to believe.

My favorite scenes had to be when Wallace was editing his mammoth novel “Infinite Jest,” sending letters to his editor and playing the editorial game, offering condensation of material as opposed to simple cutting.

There was something endearing and all-too-familiar about the manic writing process and the blurry-eyed, wishing to just get it over with sort of desperation.

His struggles with the overly-meta style of his writing and his fascination with the menial and boring parts of life seem like the perfect springboard for his Kenyon College commencement speech “This is Water” or his final novel “The Pale King.” The reason Wallace’s writing can inspire readers to be better, more attentive, more moral, is because he knows all too well the experience of being the alternative.

Max describes Wallace as a profoundly “moral” writer, though he was not necessarily a profoundly moral man. In fact, he says that Wallace’s struggle with his own morality, his own lack of attentiveness and occasional solipsism is what allowed him to meditate on those very things.

Max’s glimpse into Wallace can allow readers (especially those who happen to have that reverent view of the author) a greater appreciation for his craft.