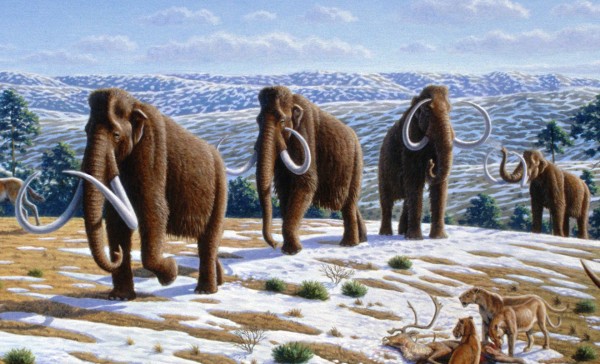

Imagine being able to bring back a herd of woolly mammoths along with a swarm of elephant birds. Within the next decade, scientists say those fantasies could become a reality.

These ideas were presented by Dr. Ross MacPhee, a curator at the American Museum of Natural History. His lecture, “De-Extinction: Is It Really Possible to Bring Back Extinct Species like the Wooly Mammoth, and if So, Should We?” was the final installment of the Harrington STEM Lecture series for the fall semester. The event was held in the Coykendall Science Building Auditorium on Tuesday, Nov. 17.

“It’s simple, it’s all about bringing back the dead,” MacPhee said. “After that, we need to have public discourse. We need to talk about it, deal with the responsibility of the returned organisms and take care of them.”

Stressing that he was not a geneticist, MacPhee spoke of his intrigue about how species disappear and if they can be brought back to life. MacPhee showed a clip from a Discovery Channel special he was involved with titled “Baby Mammoth,” which aired in 2008. The project, which he admitted was slightly far-fetched, explored the idea of bringing back not only one woolly mammoth but several herds of them.

One of MacPhee’s overarching questions was why humans should even try to bring back the dead. His answer to skeptics centered on three points.

MacPhee’s first argument was that humans have a responsibility to the extinct. He said this was his “restorative justice for all” proposal. Pointing to the common historical thread of how humans arrive and animals go, MacPhee stated that humans owed it to their counterparts. Such animals that were around but soon became victims of extinction were the giant rhinos, glyptodons, giant monitors, elephant birds and the Antillean titi monkey.

“Humans have been pillaging ecosystems for the greater extent of our existence,” MacPhee said. “We need to put everything back to the way it was before it was harmed by us.”

His follow up to that was that humans indeed have the ability to revitalize the extinct. MacPhee admitted this was not a simple solution because most of these “de-extincted” creatures would have to be placed in areas with very minimal human populations. He cited Siberia as the most likely location people point to when they discuss woolly mammoths.

MacPhee also referenced the Wallkill Valley’s previous history as a wetland of the ice age Hudson River and produced some of the best specimens of mastodons. He argued, however, that returning them to their natural home today would be impractical for farmers and residents here now.

MacPhee’s final point served as a call to justice as he stated that he believed humans could ensure other endangered species avoid extinction.

“‘De–extinction’ is never having to say goodbye,” MacPhee said.

“We’ll learn to bring back critically endangered species, like the American chestnut tree and panda bears.”

MacPhee was open about how certain methods previously attempted, such as selective breeding and reproductive breeding, led to similar creatures but not exact replicas of the host specimen. Since certain creatures are uniquely built, they require hundreds of thousands of specific traits. Both selective breeding and reproductive breeding only affect certain traits, like color, size and height, but don’t address several hundred other important and necessary traits. This produces a superficial clone but does not succeed in “de-extinction.” Citing mixed creatures as the fatal flaw of selective breeding and the premature death of Dolly the cloned sheep as the primary concern for reproductive breeding, MacPhee reached his solution: genomic engineering.

“Genomic engineering is going to change your life,” MacPhee said.

The state-of-the-art process, which utilizes chromosome synthesis, gives humans the possibility to construct genes and make whatever they would like to create. CRISPR, a gene-editing technology, combines a DNA- cutting enzyme called Cas9 with a long RNA molecule. It can also use a protein called Cpf1, which requires less RNA and slices DNA differently. The process, which was introduced after MacPhee gave a major talk in 2013, is still being heralded while being closely analyzed.

“This will allow us to make creatures that have never existed before,” MacPhee said. “The downside is that it raises some ethical issues. Whether it’s creating clones of pet dogs or designer babies, humans have to be aware of the consequences.”

MacPhee left his audience with a simple but sobering question that is likely to dominate the debate over genetic engineering for years to come.

“In principle we can do this, but should we?”