The word “mask” has taken on a political life of its own ever since COVID-19 came to the United States. Masks have become a symbol of having faith in science to some, and a symbol of blind conformity to others. “We Wear the Mask” at the Samuel Dorsky Museum of Art refers to a different type of mask. Derived from the poem of the same name by Paul Laurence Dunber, the mask that is referred to is the one we put on for others in our day to day lives, the mask that alters how we perceive others in the world and the mask that people of color wear in a world defined by white supremacy in order to survive in it.

Curator Jean-Marc Superville Sovak examines these themes of race, representation and perception through the pieces in the Dorsky’s permanent collection. Superville Sovak’s work was previously featured at the Dorsky with their “Madness in Vegetables” and “a-Historical Landscape” exhibits. In addition to his artwork being featured, Superville Sovak has held several talks at the Dorsky as an art educator.

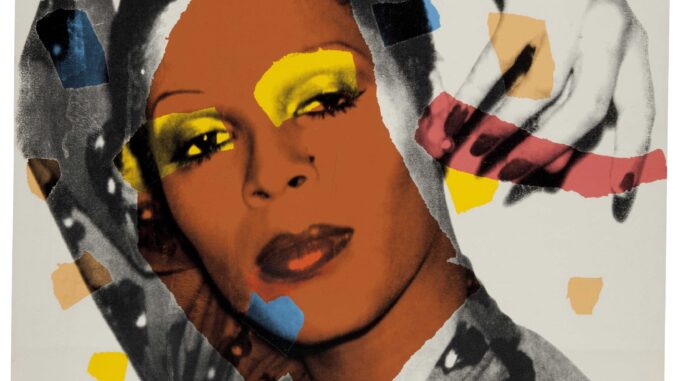

The exhibit itself features 18 selections from the 6,000 works featured at the Dorsky and covers over 3,000 years of art history, ranging “from ancient Egyptian funerary figures to polaroid photographs by Andy Warhol.” Furthermore, pieces were paired together to emphasize the juxtapositions between them for this “trans-historical, multicultural” exhibition.

Superville Sovak was asked to curate the exhibit over the summer, and the reason why they reached out to him was based on one of the most unjust and tragic events in recent memory. “Anna Conlan (Dorsky Curator and Exhibitions Manager) dropped me an email shortly after what I call the ‘lynching of George Floyd,’” Superville Sovak said. “The museum, and I think the university as a whole was really aware of how much the student body deserved to be addressed, and the issue needed to be addressed.”

“I think the way Anna expressed it, the museum as an institution on campus wanted to speak to students and visitors of color and say ‘hey, we see you’ and do something more than updating the banner on the webpage,” he continued. “She had asked me whether I would be interested in viewing the collection and curating the show through the lens of race and representation and selecting items and artwork and artifacts in the collection with the idea, with this theme in mind, and I jumped.”

The police killing of George Floyd and other Black people was in the back of his mind while combing through the Dorsky’s massive collection for the exhibition. In addition to that, two other areas of concern were on his mind while curating the pieces: the duty that artists have in addressing important issues and who exactly should this exhibit cater to.

“Cultural thinkers, producers, contributors, artists and institutions obviously have a responsibility to think about the ways in which cultural dominance of, let’s just call it Western culture, has contributed to the most visible elements of white supremacy,” Superville Sovak said.

“Then also, on sort of a more pragmatic level, the show had at least two audiences in mind. One was the institution itself, viewing itself through this prism of race and representation, which is not generally how museum collections are categorized or built,” he said. “The other audience in mind were these visitors and students of color who could enter the museum and feel like ‘oh,’ here is a way in which they might see themselves represented.”

One of the pieces that defined the focus of the exhibit was Henry Ossawa Tanner’s “The Disciples See Christ Walking on the Water.” Tanner was one of the few prominent African-American artists of the late 19th and early 20th century. He’s been described as a realist painter and his works in particular place emphasis on the luminescence and lighting of the piece, giving his paintings an ethereal quality to them.

Superville Sovak was drawn to this particular work because of Tanner’s portrayal of Christ. Christ is portrayed as a ghostly being as he’s walking on the water, making his features unidentifiable. The detail of this piece captivated Superville Sovak.

“The ‘Christ Walking on Water’ [painting] really puzzled me. As an African American artist, the question that I posed in my introduction, because it really was my first question, what biblical narrative would you want to represent?” Superville Sovak said. “The thing that struck me is that when they’re in the boat, and when they see Christ, this miracle he’s performing. They don’t actually see his face, he appears to them as a ghost.”

“Not being seen, but being seen, those are issues that make a lot of sense when talking about race and representation,” he said.

Superville Sovak’s exhibition will be at the Dorsky until Nov. 22, alongside “Dos Mundos: (Re)Constructing Narratives” and “Jan Sawka: The Place of Memory (The Memory of Place).” More information can be found on the museum’s website.