“Apples in Winter” is an experience of fierce love and the acceptance of reality. The viewer is left without a choice but to watch and receive Jennifer Delora’s performance of a mother torn between the love of her son and the reality of his actions.

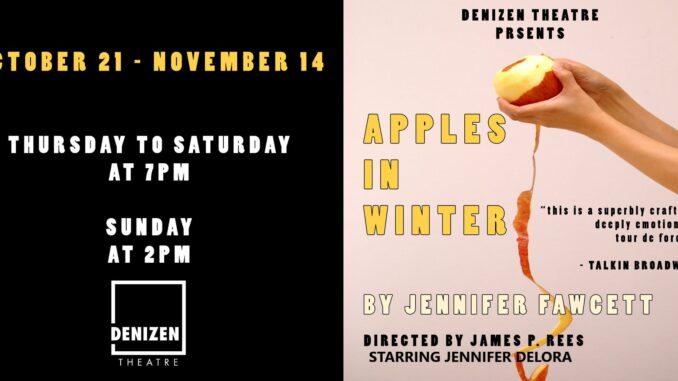

Apples in Winter, written by Jennifer Fawcett and directed by James Rees, is a one woman show set in a prison kitchen. Miriam, played by Delora, bakes an apple pie for her son Robert as his last meal. Attendees are treated to 75 minutes of rumination and introspection from Miriam as she attempts to reckon with what her son has done and what her role as his mother may have played out in his reality.

Playwright Fawcett in a Q&A after a showing of the play referenced her own headspace while creating the script. She was interested in the idea of motherhood and mothers of monsters. Also, what makes a good mother versus a bad one?

“I actually ended up writing the play while I was in the final months of pregnancy and then was the mother of a newborn,” said Fawcett, “my relationship with mothering changed massively from when I initially conceived of the play.”

This comes across as we see Miriam appear to be so deeply conflicted within herself. The worry and sadness intersects with anger.

Her son, Robert, was a drug addict prior to his taking the lives of innocent children.

She said through tears to the crowd “He scares me,” and rather than this becoming a bedrock of the play it’s more of a casing. The justification of all her years of fear and worry is seen through the very premise. He killed people and now the state will kill him.

Preparing for the role, Delora did large amounts of research. Delora said, “I looked at videos, I read articles and I also have two friends who have lost their grown children to addiction so I talked to them. It was hard.”

It was hard to watch for some as well. Fawcett mentioned the play being shown in a prison to a crowd of 100 inmates as well as correctional officers. She recounted being shocked to see grown men have emotional reactions to her work in an environment that is known for punishing vulnerability.

The reason that the audience doesn’t get to hear from Miriam’s son Robert is that his voice was seen as less necessary. Fawcett believes that the voice of a mother is one that’s “never heard” in these instances.

Rather than weighing Robert’s reasons for killing or doing drugs or causing his family unspeakable pain for decades, we can focus on his mother.

The audience can see the way she frames time by her visits with him: Her memories of locking him out of the house or her memories of lending him money.

The date Sept. 28 1998 keeps coming up in Miriam’s recollections of what happened to her son: The day he took the lives of two innocent teens was the day she in her eyes gave up as his mother. She mentions the rain and a phone call. She breaks.

“Apples in Winter” is phenomenal, aside from the fact that an actual pie is made because it feels uncomfortably real. Everyone falls somewhere on the spectrum of child or parent. Every parent carries that blinding concern for their child becoming a criminal hopefully never confirmed in their life. Each child holds that fear of disappointing their parents that hopefully never comes to pass. This play connects in a deep way because the aftermath of everything going wrong comes to pass. The dynamic is not forgotten even at its most bittersweet moments. Miriam makes her son a pie. Then he is going to die.

“Apples in Winter” is running at the Denizen Theatre until Nov. 14. It’s worth an evening out.